Gloria Guy, LEO Computer Society Committee member

My very first employment was in 1952 with Jo Lyons at Elms House and have a loose

connection with Coventry Street Corner House. Sadly, I wasn’t a Nippy but once Lyons

had trained me to use a calculator in their own training school, my job consisted of adding

up all the bills from Coventry Street Corner House – all day long! I found it fascinating

and got quite cross with Lyons when they decided to promote me after 16 months to a job

which I didn’t like and with people that I didn’t get on with!

After several moves – Bakery Sales office using comptometers, then LEO doing data

entry in 1954 I had no idea I was working on a piece of history. During this time I was

studying shorthand and typing at night school and eventually worked in their Works &

Engineering department at Spike House before leaving for a secretarial career, which

stood me in very good stead for the rest of my working life.

My mother also worked at Cadby Hall and my grandfather worked at Henry Telfer

(the meat pie company owned by Lyons). See:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/8km6dav1cr5wlq9/Gloria%20Guy%20brief%20bio.docx?dl=0

Michael Guy LEO Master Routine – The Birth of Software Engineering?

Michael Guy joined LEO straight from Wadham College, Oxford in 1962 with a

mathematics degree. After two years working on the Master Routine he left to do a PhD

at Newcastle University in integer programming. After two years working for Wiggins

Teape in their systems development department he rejoined what was then ICL. He

worked on VME for many years, progressing from programmer to designer, project

manager and OSTECH. When a team was created to pursue the UK Alvey projects,

launched as a response to the Japanese 5th Generation project, he seized the opportunity,

working mainly on persistent programming with the universities of Glasgow and St

Andrews. He ended his career with Teamware in what had become Fujitsu. On retirement

he went back to university, taking degrees in theology and biblical studies at Birmingham

University. After gaining an acquaintance with at least a dozen programming languages

he had no desire to program any more until twenty years later, when he found himself

helping to debug his grandson’s Python programs on a Raspberry Pi.

I worked on the LEO III Master Routine from 1962 to 1964, going straight from

university with a maths degree. It was nearly sixty years ago and my memories of that

time have been paged out and archived, and have probably been corrupted on the way.

Also I do not have a wide knowledge of the wider world of computing at the time. But I

have been encouraged to write this article in the hope of generating discussion of a very

important subject – the development of the discipline of software engineering.

John Daines writes “I have listings of the master routine and it was written in Intercode.

Intercode itself was a level above machine code and, although a instruction looked to be

an equivalent to a machine code instruction, it was often expanded by the translator

into several machine code instructions.

However, Intercode instructions 100/0/0 to 131/1/3 were one for one equivalents of

machine code instructions 0/0/0 to 31/1/3. That meant that the master routine

programmers could program at the lowest level and use specialist low level instructions

that weren’t in the Intercode set e.g. input output, interrupt handling, setting store

protection tags .etc

Interestingly, Cleo allowed for routines to be written in Intercode and, by implication

from the above, that Intercode might include machine code.”

LEO was the first computer to be used for business purposes. This meant a change in the

priorities of computer design. The first change was that it was used for data processing. It

spent relatively little time actually calculating and a lot of time reading paper tape,

printing and reading and writing magnetic tape. The role of the Master Routine was to

manage the computer efficiently and attempt to keep everything going full time. This is

what multi-programming is about

Michael Hancock I was Shell Mex and BP’s chief programmer when we acquired our

first Leo III in 1963 (no 6) and was involved in the studies and decisions which led to its

acquisition. We later acquired another Leo III and 2 Leo 326’s which were considerably

faster. Our computer centres were in Hemel Hempstead and Wythenshawe. Leo were in

competition with ICL and IBM and succeeded first because they had the most suitable

machine and second because of their skill in persuading our management that they were

right for the job. ICL had a grand machine on the stocks then but typically, it never saw

the light of day. I designed a massive sales accounting system with help from John Aris.

Such a pity that Leo did not have the resources to create the next generation. I was lucky

enough to be in another area while a traumatic transition to Univac took place.

The Leo users group brought me into contact which such as Dunlop and Imperial

Tobacco. The latter was worth a visit to Bristol as they gave away a box of cigarettes to

their visitors. An extended version of the career and memoirs is available in Dropbox at

https://www.dropbox.com/s/22dwf6tv7cid0ui/Mike%20Hancock%20Memors.docx?dl=0

Douglas Hartree and LEO (from Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Hartree)

Hartree’s fourth and final major contribution to British computing started in early

1947 when the catering firm of J. Lyons & Co. in London heard of the ENIAC and sent a

small team in the summer of that year to study what was happening in the USA, because

they felt that these new computers might be of assistance in the huge amount of

administrative and accounting work which the firm had to do. The team met with Col.

Herman Goldstine at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton who wrote to Hartree

telling him of their search. As soon as he received this letter, Hartree wrote and invited

representatives of Lyons to come to Cambridge for a meeting with him and Wilkes. This

led to the development of a commercial version of EDSAC developed by Lyons, called

LEO, the first computer used for commercial business applications. After Hartree’s death,

the headquarters of LEO Computers was renamed Hartree House. This illustrates the

extent to which Lyons felt that Hartree had contributed to their new venture.

Hartree’s last famous contribution to computing was an estimate in 1950 of the

potential demand for computers, which was much lower than turned out to be the case:

“We have a computer here in Cambridge, one in Manchester and one at the [NPL]. I

suppose there ought to be one in Scotland, but that’s about all.” Such underestimates of

the number of computers that would be required were common at the time!

Presentation Friday 26 April, 2024 at 17.00 BST by Andrew Herbert on the EDSAC Rebuild at TNMoC. A recording is available here Zoom Recording.

Andrew commented the following in the abstract.

While EDSAC can justifiably claim to have been ‘the world’s first practical digital electronic stored program computer’, as is well-known to the LEO community, Pinkerton, Lenaerts and colleagues had to address many of the ‘inadequacies’ to produce in LEO a robust machine that could take on the information processing needs of the Lyons company and be the world’s first successful business computer.

Andrew Herbert: The EDSAC Rebuild at TNMoC Read More »

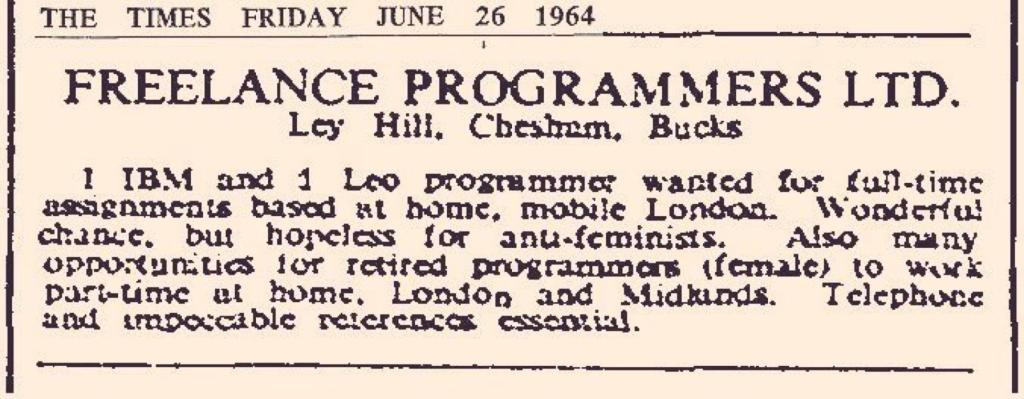

In 1964 the inimitable Dame Stephanie ran this advert in The Times, seeking programmers for her startup. “Ant-feminists need not apply”-plus opportunities for women who’d retired

Marie Hicks Twitter Message: Read More »

Denis Hitchens. Operator on LEO III/15 at Shell Australia

Neil Lamming interviewed me and conducted the aptitude test. But the person I was

really trying to dredge from my memory was Bill Cheek who along with Jack Dankert

encouraged me to return to full-time study. I was 19 and 20 at the time, turning 21 about

a fortnight before I went to RMIT — imagine a 20 year old shift leader with the fate of

SCO in his hands!! So for me as a whippersnapper training 35+ year olds was a life

defining experience and one which a bit later in life when I was President of the Students’

Representative Council (elected leader of some 12,000 students) I was able to refer to

when addressing Melbourne Rotary ( yes, all the big wigs). A fuller version of the

reminiscences are available in the LEO Dropbox archive at

https://www.dropbox.com/s/bqgrbhxh9cp4s4k/Denis%20Hitchens%20Reminiscences.docx?dl=0

Brian Hobson: I am glad that you, (Hilary Caminer), were able to attend our recent

“LEO do” as chaotic as it was! You asked if I would explain the origins of our group and

also to help you understand our Lyons/LEO relationship as it seemed rather confusing.

I will do my best. The meeting started when Norman Beasley retired from Lyons

in/around 1982. Norman had been a member of Lyons/Leo from the early days and was

Operations manager on LEO 1, LEO II/1, and LEO III/7 before becoming Computer

Consultant to the Lyons group of companies.

Norman lived in Chalfont St Giles (I think this is correct) and Peter Bird (Lyons

Programming Manager) and Alex Tepper (Lyons Operations manager) would go to visit

him fairly frequently. Carol Hurst, who was at our meeting, also lived nearby and had

also left Lyons would join the others making a foursome. In my Lyons career I started in

Operations as an operator (employed by Norman) and later became a consultant working

with Norman. When Alex Tepper was promoted to Head of Computing for Lyons I

became Operations manager and joined the gathering.

All Lyons computer staff are quite a close knit group and various members moved into

senior positions within other companies within the group as Accountants or Head of

Computing, etc. Tony Thompson, who you met, became Chief Accountant for various

companies, Alan King (now passed away) became head of Lyons Maid computing. They

joined in our meetings and gradually as time went on our group has continued but with

varying members, as old ones passed away others came to know of us and joined. Peter

Bird was the mainstay organiser as he had the most contacts. Cyril Lanch is a fairly

newcomer to our group but did not step back quick enough when volunteers were sought

to carry on Peter’s organising! Hopefully that explains our group, now for the

LEO/Lyons feelings – difficult!

History of Lyons and computers. Lyons built a computer to do work for Lyons Electronic

Office (LEO), staff working on the computers were Lyons staff. With the success of

computers Lyons formed a computer company LEO Computers Ltd but the staff although

working for LEO were still Lyons staff at heart. When the company LEO was sold the

computers remained at Lyons and were operated by Leo staff until they chose to remain

at Lyons or were replaced by new Lyons staff.

Lyons computer history goes from LEO I through Leo II/1, LEO III/7, LEO 326/46 and

eventually to IBM computers. Our attachment to LEO may be explained by the fact that

the original computers were still in use at Lyons long after LEO had been sold and in

many instances the staff working them were the original staff. When LEO was sold the

computer department became LEO and METHODS, then Lyons Computer Services Ltd

(LCS My best analogy would be: If you had a daughter and she got married she would

still be your daughter and a member of your family although she would have joined

another family, you would continue to be proud of her. The same is how our computer

department feel.

When LEO was sold the computer department became LEO and METHODS, then Lyons

Computer Services Ltd (LCS), and finally Lyons Information Systems Ltd (LIS).

As you may now gather we were very proud of our heritage but so was the computer

industry. We as a Computer Bureau (which we had been from day 1 of computers)

strived to continue to be at the forefront of computer usage and computer and peripheral

manufacturers were very keen to be associated with us offering us very competitive deals

to use their equipment. Our computer department was frequently put under the

microscope by the main Lyons Board as the newer family Board members felt that

computing was expensive but on every occasion the auditing companies, including IBM,

were in awe as to how we are able to do so much with so little and still lead the

world. An example of this was back when Lyons had a fire on the Xeronic Printer in the

LEO III/7 computer room. We made an arrangement with the Post Office (as it was then)

to use their LEO III (overnight) in Charles House which was just across the road from

us. Our shift of 6 operators replaced a shift of 20+ operators.

I cannot remember the trade magazine that did a piece on us as we were the first company

to wire an entire building with various departments on different floors to use Local Area

Networks linked into the mainframe. Also, one of our external customers was a large

American personal tax company which had a large computer centre in the States but

wanted a worldwide centre based in London. We installed a duplicate of their system

onto our computer, they provided no computing staff as all maintenance etc. would be

done from the States we only had two user/managers with us. Their system was difficult

for their users to manage and I spent a lot of time supporting them because of the

complexity of their system.

Eventually I volunteered to improve it for them and wrote a few simple programs

and restructured their system making it much more efficient (saving hours a day of

machine and their input time). The computer staff in America were interested in what I

had done and came over to see for themselves, they were amazed and the CEO asked

permission to adopt our version of their system to replace their own!

My own involvement with Lyons started while I was at school. My brother, Colin, whom

you met was an operator at Lyons on LEO II/1 (but employed by LEO Computers) and I

used to go with him to work some evenings or when I was not at school. I was able to

help operate the LEO II computer (unofficially of course) and met the engineers on the

LEO III/7. When Colin moved to Hartree House I also used to go there as well and

helped out on the LEO III installed there. I loved the job and it really appealed to me so

when I left school (in 1966) I went for interviews at Lyons and ICT (as it was

then). Norman interviewed me and offered me the job (it helped that I knew several of

the staff by name which impressed him!). I worked my way up from trainee operator to

Ops Manager until the closure of the company in 1991. I won’t bore you with my life

history of the roles I held and of the changes in company structure that I made over the

years as most of this was during our IBM period.

I hope that this gives you some insight into our little group and our attachment to LEO

and why we feel a little side-lined when at the LEO Computer Society gatherings Lyons

seems to be irrelevant. Maybe that is changing now but at the few meetings I went to

over the years that is how it seemed which is why I have never bothered joining

Colin Hobson: Weather, Wildlife and LEO Computers

Both LEO 1 and the LEO 2s were not installed in cosy, air-conditioned palaces. They went

into normal office accommodation and the heat, generated by the hundreds of thermionic

valves was conducted away by fans and overhead ducting. The operators were kept cool

only if they could open the office windows! This could cause a number of unexpected

problems:

On LEO 1 rain could be a problem. It was necessary to look outside before turning

anything on. If it was raining, or snowing, the heaters in the valves needed to be turned on

before the cooling fans. This built up enough heat to ensure that the water droplets sucked

in were vaporised before they hit a hot glass valve cover. Failure to do it this way round

would result in a series of high pitched squeaks as the glass, of the valves cracked. This

would be followed by the sound of engineers swearing! If there was no rain, it was better

to get the cooling up and running first.

On LEO 2 this was not a problem. The ventilation system didn’t cause the computer much

in the way of problems. The computer did provide a lot of heat, most of which was

conducted away by the ventilation system. However, there was still a lot of peripheral

equipment and human bodies churning out heat. The only option, certainly on LEO 2/1 was

to open the windows to the outside world. Mostly this worked well. However, there were

times when the outside world made its way into the operating area to cause chaos. Wildlife

was one such problem. The occasional visiting bird could provide some distracting

entertainment but the worst problem I can remember was a swarm of small insects which

came in through the open windows and settled on the paper tapes and punched cards. They

got squished into the holes in the cards and tapes changing the data.

Many years later I was working at a Post Office (now BT) site where a snake made its way

through one of the doors from the outside world, down a short corridor and then got stuck

between the automatic airlock doors into the air-conditioned computer hall.

Colin Hobson adds I was worked on LEO 1 and subsequent machines but am not sure

about recordings. LEO 1 certainly did make a noise but I have a vague recollection that

the speaker was not in the original hardware but in the dexion operators console, which

was a later addition.

LEO 1 was on a platform at one end of the room (hall). There was an engineer’s console

up there which the operators did not use. The dexion operators console was down on the

parquet flooring along with all the peripherals. The peripherals were aligned in two rows

with shallow metal cable runs going back to the main frame platform. The room was not

air conditioned and at times it was necessary to open several windows to allow the

operators to breathe! A warm wet day was a real problem as we had to make sure the

heat in the room was enough to evaporate the rain before we could open the

windows! Another side effect, on the operators, was the smell of cooking which often

wafted up from below!

Note: Colin Hobson was interviewed by Marie Hicks for her book Programmed

Inequality (see above) and provides one of her case studies noting the story of LEO